THE RACIAL WEALTH GAP: THE CHASM THAT JUST WON'T CLOSE, PART II

Jesus is reported as having said: “The poor will always be with you.” Putting aside hermenuetical squabbles over exactly what he means here, Jesus’ utterance certainly seems to paint a picture wherein poverty is persistence.

Even today, thousands of years after Jesus is reported to have uttered these words, the World Bank estimates that 648 million persons, approximately 8% of the global population, live on less than $2.15 per day. That same World Bank report also notes that if we use a higher benchmark to measure poverty, then the number of poor persons worldwide increases dramatically: Almost half of the world’s population (47%) survives—if that’s what you want to call it— on less than $6.85 per day.

And in the United States, one of the richest countries in the world, the number of people in poverty clocks in at almost 40 million or around 11.6% of the population.

But what Jesus is reported to have said about poverty, we could also add a similar saying about the racial wealth gap, a gap that seems to be extraordinarily resistant to erasure:

“The racial wealth gap will always be with you.”

Speaking of the racial wealth gap and its persistence, this brief post is part of a series of portraits and explanations of the persistence of the racial wealth gap. The focus in on a study of long-run trends in the racial wealth chasm carried out by the economists Ellora Derenoncourt, Chi Hyun Kim, Moritz Kuhn, and Moritz Schularich. In fact, this is the second post in the series that touches on the findings of this extremely important study (to read the initial post click here).

So, the heads up is this: First, I’ll recall what this team of economists finds to be the overall shape or trajectory of the racial wealth gap between 1860 and 2020. Second, I’ll highlight their explanation of why the most dramatic and rapid decline in the racial wealth gap occurred within the first several decades of the post-emancipation period. Finally, I’ll tee stuff up for the next installment in this series.

THE HISTORICAL TRAJECTORY OF THE RACIAL WEALTH GAP: A QUICK RECALL

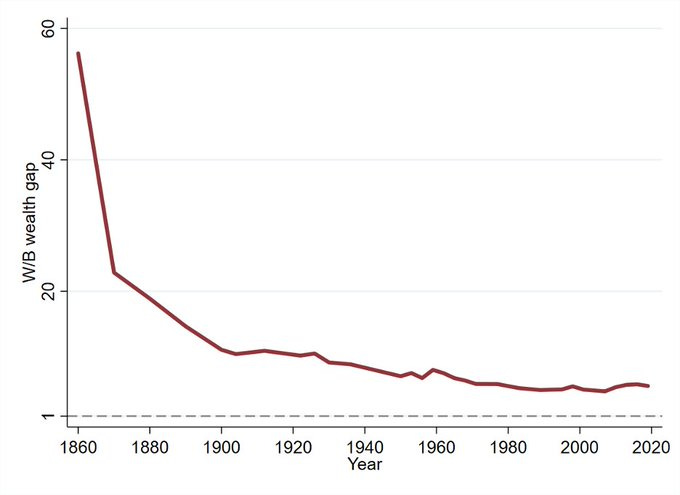

Dr. Derenoncourt and her colleagues find that, between 1860 and 2020, the path of the White/Black wealth gap resembles the shape of a hockey stick:

The time span runs from pre-emancipation (1860) to a fully matured capitalist economy.

Starting from 1860—and this was noted in the previous post— the authors find the White/Black racial wealth gap clocks in at almost 60:1. In other words, Blacks held less than two cents in wealth for every dollar possessed by Whites.

By 1870, though, the authors find a steep decline in the White/Black wealth ratio. More specifically, between 1860 and 1870—a mere ten years— the White/Black wealth ratio slid from almost 60:1 to 23:1. Over the 1860-1870 decade, then, Blacks went from holding less than 2 cents (1/60) to holding almost 4.5 cents to every dollar of wealth held by Whites.

Take another look at the graph and you’ll see this: The team of economists estimate that the White/Black wealth ratio declined to 10:1 by 1920, with Blacks now having ten cents for every dollar of wealth possessed by Whites (1/10).

What’s more, by the 1950’s the racial wealth gap had closed even further, with the White/Black ratio dropping to about 7:1 or, what amounts to the same thing, with Blacks having 14 cents for every dollar of wealth held by Whites.

Since the 1950s, however, the racial wealth ratio has ceased closing and, since the 1980s, has even reversed course and started to widen.

Here’s how they summarize the trajectory of the White/Black wealth ratio:

Our data show that the most dramatic episode of racial wealth convergence occurred in the first 50 years after Emancipation. This initially rapid convergence gave way to much slower declines in the wealth gap in the second half of the 20th century. From a starting point of nearly 60 to 1, the white-to-Black per capita wealth ratio fell to 10 to 1 by 1920, and to 7 to 1 by the 1950s. 70 years later the wealth gap remains at a similar magnitude of 6 to 1.

There’s a lot here. We’ll get into a good deal of that in subsequent posts. For the moment, though, I want to call your attention to one of the issues that’s the specific focus of this focus: These researchers, as they point out in the above quotation, find that the most dramatic decrease in the racial wealth gap occurred during the first five or six decades after emancipation.

To reiterate, that convergence is reflected in a steep drop in the White/Black wealth ratio, from almost 60:1 on the eve of the Civil War to 23:1 in 1870 following emancipation to 10:1 in 1920.

What accounts for this deep descent in the White/Black wealth ratio, especially that steep slide between 1860 and 1870?

ACCOUNTING FOR THE DESCENT

The deep post emancipation descent in the White/Black wealth ratio is attributed to three factors.

First, the abolition of slavery reduced one source of White wealth— namely, the wealth of slaveholders that derived from their enslavemment of Black labor. Everything else being equal, the abolition of slavery reduced the numerator in the White/Black wealth ratio and, as result, reduced the size of that fraction. As Derenoncourt and her colleagues put it: “The abolition of slavery in the U.S. eliminated what wealth slaveholders held in enslaved individuals.”

Second, the abolition of slavery opened up more opportunities for Blacks to earn, save, and purchase land. Taking advantage of this as best as they could, Black wealth, although still relatively meager, ticked upward. Everything else being equal, the authors reason that an increase in the denominator—per capita Black wealth— resulted in a decrease in the White/Black wealth ratio (remember: a decrease in this ratio signals a decrease in the racial wealth gap.

Of these two factors— a decline in White slaveholder’s wealth and a relatively more rapid accumulation of wealth— it’s the latter that’s found to have had the greatest impact on the racial wealth gap that took place between 1860-1870. On this point, the authors state:

The abolition of slavery in the U.S. eliminated what wealth slaveholders held in enslaved individuals. It also afforded the formerly enslaved an opportunity to accumulate wealth for the first time. How much of the decrease in the wealth gap in the decade of the Civil War can be attributed to the elimination of slave wealth versus wealth accumulation by the newly emancipated? Using an estimate of total slave wealth from the Historical Statistics of the United States (Sutch, 1988), we calculate that slave wealth made up around 15% of total wealth in 1860.16 If we subtract slave wealth from white wealth in 1860, the wealth gap falls from 56:1 to 47:1. Thus, all else equal, eliminating slave wealth would reduce the gap by 9, or 25% of the total drop of 34 (from 56 to 22). In other words, slave wealth cannot account for the entire reduction in the wealth gap from 1860 to 1870. Instead, it is the higher relative growth rate of Black wealth that drives convergence.

Third, the rapid decline in the White/Black wealth ratio between, say, 1860 and 1870, is partly a mathematical artifact. The team of economists that put that work in and produced this study makes a point of emphasizing that when one group—like Blacks— start out with little to no wealth, then even small increases in its wealth holdings will have an outsized impact on the White/Black wealth ratio. (To hear a very informative interview with Dr. Derenoncourt, click here).

Just think of it this way: In 1860, Black folk had very little capital. In fact, 90% of the Black population were capital. Thus, even a small increase in the amount of Black wealth translates into a big percentage increase and thereby result in a massive narrowing of the racial wealth gap.

Like Derenoncourt and her colleagues, several commentators have called attention to the way in which the trajectory in the racial wealth gap reflects an underlying statistical logic. As one reviewer recently put it:

This convergence, however, is more a matter of statistics than reflection of meaningful economic or political change. Because Black Americans’ wealth was so low in 1870, even small gains translated to big percent increases in wealth and thus large reductions in the wealth gap, even though the difference in the amount of average wealth held by Black Americans and White Americans remained large.

RECAP AND LOOKING AHEAD

So, what we’re left with is this:

Most of the decline in the racial wealth ratio occurred between 1860 and 1920.

The most rapid decline occurred between 1860 and 1870, with most of that reflecting: 1) increased accumulation of Black wealth during Reconstruction and 2) the mathematical logic that underlies movements in ratios

Despite the relatively large percentage decreases in the White/Black wealth ratio, Blacks still earn pennies on every dollar of wealth held by Whites

The closing of the racial wealth gap had pretty much ceased by the 1950s

Since the 1980s, progress toward convergence has reversed and the racial wealth gap has started to widen

In the next post, one of the things I’ll pick up on is how the authors explain the more recent widening of the racial wealth gap.

Hang in there, kinfolk!

Comments